On “The Nobody zone” and the importance of archives

I have recently enjoyed listening to the podcast “The Nobody Zone” by RTE Doc on One and Third Ear Productions. Enjoyed is a relative term, as the podcast uncovers the harsh and lawless life of the homeless in London, and especially the life of many Irish migrants. But the podcast is brilliant in so many ways, and it inspired me to write about the importance of archives. If you haven’t listened to it already (and you should!), it centers on Kieran Kelly, a homeless Irishman who killed at least two people, probably more, in London. He was in and out of prison and mental institutions and was acquitted of murder and murder attempts, before being convicted of two murders in the early 80’s and sentenced to life. He died in 2001.

One of the things I loved most about the podcast, is that they talk a lot about HOW they find information. The series is well-researched, and we are taken on a journey spanning several decades, from the rural Midlands of Ireland in the 1930s, to descendants of Irish immigrants in today’s London. The podcast would not have been possible without the information gleaned from public records and archives. Luckily, some of the institutions have well-kept records that allow the journalists to find long-forgotten pieces of important information. Other lines of inquiry simply come to an end because the relevant archives have been thrown away. This is the case with some supposed suicides on the London underground from the 60’s and 70’s: Coroner’s reports have been destroyed to save space.

How is this relevant to archaeology?

Most of us archaeologists will work with archives at some point in our career. We might work with finds and excavation reports from the 19th century or even earlier, and it is crucial that these are preserved and accessible.

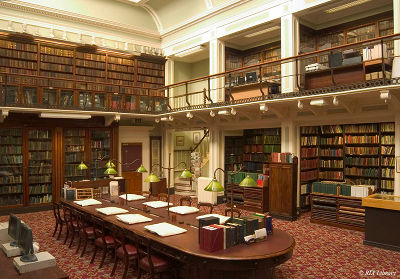

I spent a lot of time researching the Irish Viking-age silver hoards and their locations. Finding information about the exact location was crucial to prove that the hoards were in fact found in connection to Irish and Norse settlements, and not in remote locations away from settlements. This would not have been possible without reading the descriptions of the finds in archives. Much time was spent in the Royal Irish Academy library in Dublin and the topographical archives at the National Museum of Ireland. The topographical archive is typical of museums, where finds and information are sorted by counties and placenames. Many of the finds were never reported to the museum, and the only information about the find is a short description in 19th century publications by the Royal Irish Academy. If these records and archives were lost, the research would not have been possible.

Why is destroying archives a bad idea?

The destruction of archives should simply not happen. If keeping the actual physical records is not possible, it should be mandatory to digitalize the documents so that they are preserved that way. One might say that being unable to do archaeological research is not the end of the world, but this has repercussions for everyone. Documents pertaining to your social welfare and health might be destroyed or not kept or made in the first place.

A tragic example is the destruction of documents relating to immigration to the UK from the Caribbean Commonwealth colonies. Many people lost their only proof of entry to the country, and now risk not having legal status and citizenship in the UK. All because their disembarkation cards from the 50’s and 60’s were purposefully destroyed, despite the warnings from caseworkers at The Home Office. The Immigration Act of 1971 granted indefinite residency to people who were in the country at that time, but a registry of who this concerned was never made. A person’s arrival date is crucial to a citizenship application, but according to the more recent, stricter immigration rules people need to prove their residency. But how can they when the government destroyed the proof? People of the so-called “Windrush-generation” have been denied passports and even cancer treatment. Read more:

Sometimes archives are deliberately destroyed to hide the truth, as with the willed destruction of sensitive papers from Britain’s late colonial era to hide knowledge of crime and repression from post-independent governments and prevent this information becoming public, as reported by The Guardian:

Britain destroyed records of colonial crimes | National Archives | The Guardian

Revealed: the bonfire of papers at the end of Empire | National Archives | The Guardian

Conclusion

Archives matter to all of us, especially to those already marginalized. They matter to journalists and they matter to researchers of all disciplines. Archive destruction can have dangerous effects on people’s lives. Archivists make decisions as to whether to keep or throw away all the time, and archivists in Norway have already warned that they need help from researchers, such as historians, to decide what they/we need to keep, in order to do research in the future. Especially considering that most archives now are digital. Read more: Teleskopet til fortiden (forskerforum.no)

Sometimes, the documents in the archives can be the only source of information. A fire in the Danish national archives in Copenhagen in 1728 destroyed important documents, including the archives from the great Norwegian monasteries on their property and holdings. One of the reasons we can research monastic history today, is because the Danish steward in Norway at the time realized the need to create a registry of the old monastic documents. He contacted the Danish king, who sent two scribes to make a registry of the monastic archives before they were sent from Oslo to Copenhagen in 1622. This record, “Akershusregisteret”, survives and is an important source to monastic history in medieval Norway. Archives for the win!

Linn Marie Krogsrud is a Norwegian archaeologist. She works as a heritage advisor for Buskerud County Municipality and is a member of ArchaeologistsEngage.