Introduction

This article is based upon a presentation given to the 2021 Conference of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA). It is written for an English archaeological context. To introduce myself, I’m a Senior Heritage Consultant with MCIfA accreditation at an environmental and design consultancy called Arcadis. I’d like to begin by setting out briefly how my career developed in order to provide some context, following which there are a number of strands of thought I’d like to bring together that I think are important to the discussions of chartership and developing the profession.

I graduated from Trinity College Dublin in 2006 with a BA in Ancient History and Archaeology and History of Art and Architecture. While the course title was a quite a mouthful, it came with the delightful abbreviation of AHA HAA which may tickle those of you who have the same terrible dad-joke sense of humour as myself.

I worked for a commercial archaeological company (Headland Archaeology) in Ireland for two years as a field archaeologist and a post-excavation archaeologist, following which I lost my job in the financial crash of 2008. I moved to the UK in 2010 and spent two years working as a field archaeologist for a commercial archaeological unit (Cotswold Archaeology). At the cusp of achieving site supervisor level, I decided for various reasons to change career path and moved to the consultancy department where I spent another two years.

In 2014 I went to work for engineering firm URS which soon after was taken over by AECOM, a similar company. In 2016 I took up a post with Pegasus Planning Group where I worked until 2019 when I took up my current role at Arcadis. In summary, I have had a varied career across two countries which has included commercial archaeological fieldwork and consultancy. The companies I have worked for included commercial archaeological units (some doubling as charitable organisations), engineering/design and environmental consultancies and a planning consultancy.

In this time, I have also taken up a fair few extra-curricular activities including volunteering on a University of Bristol excavation in North Carolina in the USA and acting as Excavation Co-Director for Project Nivica Archaeology in Albania (affiliated with the Cultural Heritage Institute of the Royal Agricultural University). In 2020 I joined the charitable organisation ‘Archaeologists Engage’, an international group which is focused on promoting public engagement in archaeology, by undertaking advocacy within archaeological circles and providing archaeologists with the tools to undertake outreach, as well as organizing direct engagement with the public. I subsequently became a Trustee of the Bristol and Avon Archaeological Society with the aim of contributing to greater public engagement with archaeology in my adopted home of Bristol.

Joining CIfA

I joined CIfA relatively late in my career. Although I had aspired to join for many years during the consultancy phase of my career, I only joined in 2021 at MCIfA level. I think that the main reason I took so long to join was that I often felt pressured or obligated, at times both by myself and external sources, to try to go in straight at MCIfA level. For a long time I was just not ready for that and as a result I started work on an application multiple times only to run out of steam or hit a mental brick wall and not finish it.

With that experience, my advice would be that having any level of CIfA membership is very worthwhile and there is nothing wrong with applying for a grade which comfortably fits your experience level. If you have staff junior to you who want to join CIfA then think about encouraging them to apply for a grade that they can easily get rather than shooting for the highest one possible. They can always upgrade later and there is nothing to be lost by that approach.

In the next sections I will discuss my take on what makes a professional, what chartership means for archaeology and my thoughts on some aspects of the chartership proposals. Then, I will finish up by highlighting areas where we need to improve as a profession, particularly in the context of chartership.

What Makes an Archaeological Professional?

An archaeological professional in the consultancy sphere is someone who has to walk a tightrope on a daily basis. We constantly have to strive to achieve a balance between powerful competing forces. On the one hand, the professional obligation to conserve heritage assets, and on the other our professional obligation to do a good job for our clients. On some lucky occasions these needs align, but more often than not we have to maintain that delicate balancing act between the two.

At different times in my career I have been pulled too far in either direction, and as a result I must be honest and say that I have not always made the right decision in the past. It is only with the benefit of a number of years’ experience under my belt, and the confidence that brings, that I have been able to consistently maintain the balance of professional ethics and to actively push for better outcomes for all sides. I think that this experience and earned knowledge, along with an awareness of the need for balance, are crucial factors in being an archaeological professional in this career pathway (and others too of course, not least commercial archaeological fieldwork).

Another crucial element of being a professional is an understanding of the wider context in which our work is taking place. That context can be of legislation and policy, the particular requirements of a client or council officer, or the impacts that heritage conservation can have for other disciplines such as ecology. This is something which is already widely accepted to be the case and is already accounted for in attaining MCIfA accreditation. I bring it up because this awareness of wider context is something which we as a profession need to develop further, a concept which I will return to shortly.

Why do we want to be chartered?

Generally, we want to become chartered in order to promote recognition of the archaeological profession to the public and to achieve parity with other professions. We should definitely be striving to achieve parity with the other specialists we regularly work alongside, such as geologists or architects, and the previous votes for chartership indicate that most archaeologists agree with this. Certainly, our advice to developers would have more weight when it is seen coming from a chartered professional, something which is not so easy to dismiss. In the chartership proposals there were some mentions of the public and wider society, but nothing concrete. I think that there is a bit of a gap in our aspirations here, which I will discuss in more detail shortly.

How to Become Chartered

A lot of ink has been spilled on this and many people have put forward their viewpoints, so I will just touch on this briefly. While most of us agree that chartership is an important goal, where we have come unstuck is articulating what it means to be a chartered archaeologist and how that should integrate into the existing CIfA framework. The previous proposals, voted down by CIfA members, proposed establishing chartership as a new rung of the ladder added above MCIfA level.

Chartership is a terminal qualification within a profession, but the terminal qualification up to now has been MCIfA. Chartership is an external recognition rather than a specified set of requirements, so it does not seem entirely logical that how we define the terminal qualification in archaeology should now have to radically change. For example, I have outlined previously how professional ethics are already a core pillar for archaeological consultants operating at MCIfA level and there is not a higher level of ethics existing above this.

What this boils down to is that chartership is equivalent to MCIfA but that the logistics of merging the two is extremely difficult. However, a failure to effectively and convincingly tackle this issue, appears to be one of the main reasons that the previous proposals failed to convince the necessary number of CIfA members. How we overcome this issue is an entirely difficult and detailed discussion beyond the scope of this article, so I will move on to other points I’d like to discuss.

What should chartership mean?

I don’t think that achieving chartership will automatically translate to increased awareness of the value of archaeology, something which is highlighted in the previous proposals, although it will certainly lead to greater professional recognition of archaeologists by those working in other professional sectors. To promote greater awareness of the value of archaeology we need to look outward, not inward. The proposed English Planning Reforms mooted by the UK government in 2021 should be a wake-up call to the entire archaeological sector. It is all too easy to let the NPPF become your entire world, but we need to take a step back and remember that archaeology is about much more than current policy, and that policy supports can be pulled out from underneath us at any time.

We can’t simply carry on assuming that archaeological protections will always be there. We can’t assume that the legislative and policy basis which creates the environment in which we define our professionalism will always be there. One of CIfA’s most important roles is lobbying and advocating for archaeology, something which it does well and should be commended for. However, lobbying politicians will become pointless without having public support behind archaeology which will force those politicians to act.

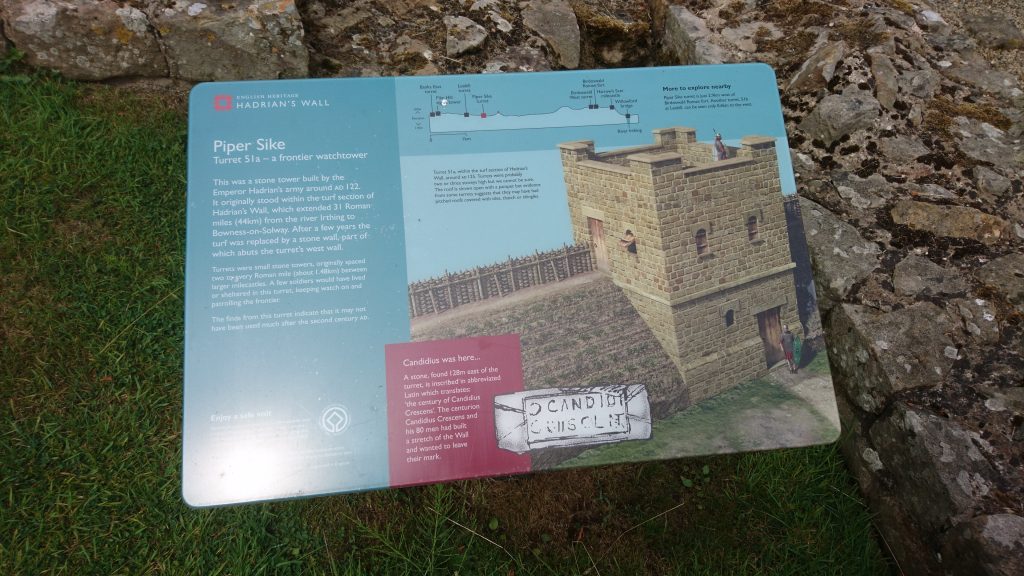

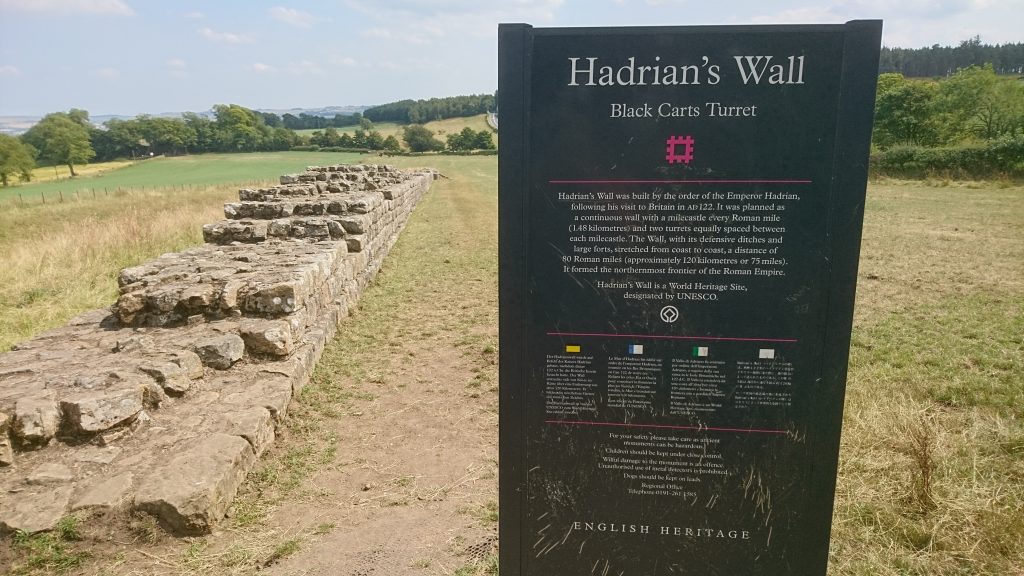

I challenge the archaeology sector as a whole to consider that public engagement should be a core tenet of what it means to be a chartered archaeologist. Some people might rebut that other chartered professions focus on the professional working sphere only and don’t worry about public engagement. This is true, but archaeology is not like many of the other professions that are already chartered. The value of good engineering standards is readily apparent to all – if we reduce engineering standards and protections then structures might fall down. Anyone can understand why that would be bad!

Archaeology, however, needs to constantly prove its worth, appeal to new generations and harness public support to push back against attempts to water down archaeological protections. I acknowledge that this is a simplistic depiction of nuanced issues and that other sectors can face somewhat similar issues (ecology for example), but for archaeology it is clear that promoting public understanding of its value is of paramount and central importance to our profession.

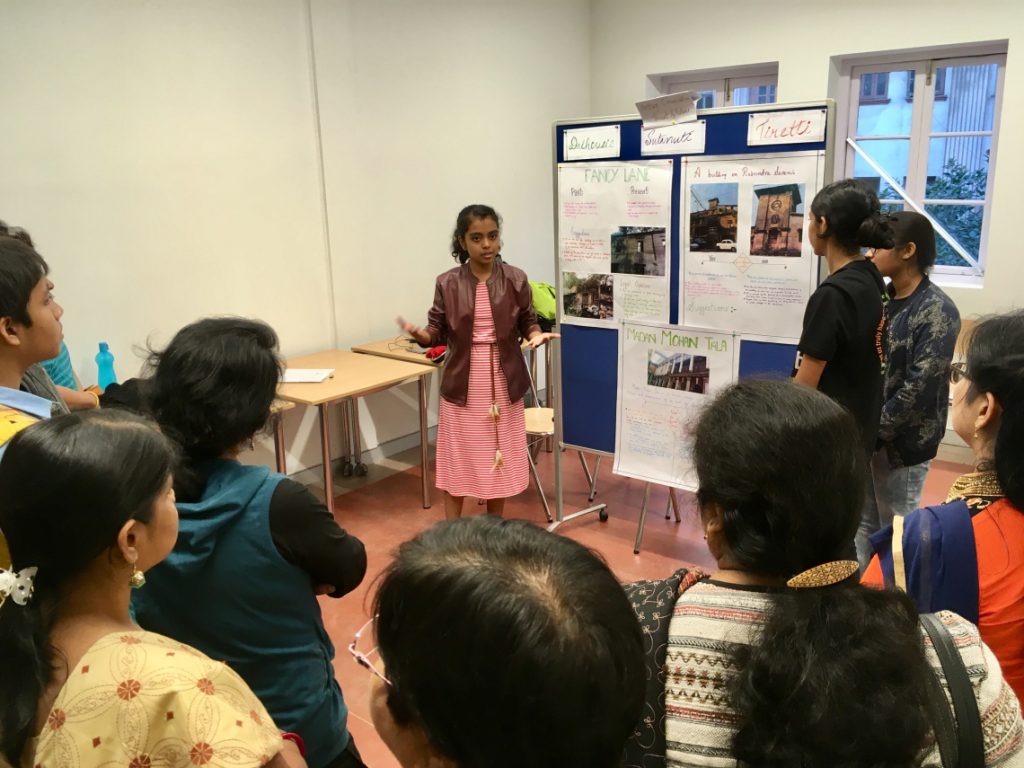

It is simply not good enough for professional archaeologists to sit back and focus on only the professional sphere, leaving all the heavy lifting of public engagement to other parts of the heritage sector (often voluntary or poorly-funded). We need to all pull our weight and do our part to ensure that public support remains behind archaeology, so that our heritage stays protected and we can all keep doing the jobs that we value so highly. Consultants in particular should not run screaming from the mere mention of “communal value” of a heritage asset! Our jobs in consultancy would not exist without the outreach and engagement work being done by archaeologists in other career paths, including volunteering archaeologists and enthusiastic amateurs. I must stress here that there are many professional archaeologists already doing outreach and my comments are not intended to take away from the great work which is already taking place!

So, I think that we need to move forward with conversations on how we can better integrate the concept of engagement into chartership – whether it is merged with MCIfA level or whether it becomes an element which distinguishes a separate chartership level from MCIfA. Engagement requirements could be integrated with the regular proposed reviews of CPD for chartered archaeologists which was suggested in the previous proposals. What form this engagement should take, whether it is simply promoting archaeology on Social Media, getting involved in a local society or making our clients more aware of the positive benefits of engagement, is something which needs to be debated and discussed in more detail.

Accessibility and Diversity

Moving on to another important point for the future of the discipline, which is accessibility and diversity. The archaeological sector has a problematic lack of diversity, and in consultancy the issue is so severe that it makes the rest of the sector look good. As university educations become more expensive and less accessible to some groups of people, it is good to see that non-university routes into archaeological careers are being explored, most notably via apprenticeships schemes. I think that these routes need to be developed further in future and that it is very important for CIfA to lay out a clear career pathway from apprenticeship or NVQ through to chartership (which I understand is currently being developed).

I don’t think that it is fair to exclude archaeologists with extensive field experience from attaining chartership because they did not have the opportunity to go to university. I also do not think that the lack of a university degree should prevent someone becoming a project officer, archaeological manager or a consultant, provided they can demonstrate that they possess the necessary skills and experience to do the job.

Concluding Thoughts

Well done if you have made it this far in the article (although I understand if you may have skipped to the end!). In summary, I think that we should be striving to attain chartership for individual archaeologists across different career paths and that as a sector we all need to look up from our individual trenches to better understand our wider context and to do more to promote archaeology as a whole to the public. After all, archaeology is all about people and without them, what’s the point?

Donal Lucey is an Irish archaeologist with a background in commercial fieldwork in the UK and Ireland. His particular areas of interest are the transition from the Late Roman Empire to the Early Medieval period in Britain and the development of early Christianity in North-West Europe. Donal is passionate about promoting public engagement with archaeology and increasing the accessibility and diversity of archaeology as a profession.