One of the most ambitious projects that Heritage Walk Calcutta has been itching to take on is engaging students in heritage conservation. As a part of the three-day FUTURE (T)HERE International Youth Conference On Sustainable Living 2018, Heritage Walk Calcutta’s team worked with kids from Calcutta, Guwahati, and Kharagpur, discussing the legalities of conserving Calcutta’s built heritage. This conference, hosted by the Goethe Institut, Kolkata, was a perfect opportunity to help the students question the definitions and facts and rote learning that are often the bane of history classes. Asking individual students about their own understandings of words like ‘heritage’, ‘community’, ‘sustainability’, ‘conservation’, or ‘ownership’ — and even ‘old’, ‘ancient’, and ‘modern’ – brought to the fore the general confusion around what heritage means. The fact that Grandma’s old recipe book can also be a part of an individual’s heritage helped them come to terms with ideas of private and public ownership of heritage, and how ‘old’ things or ‘ancient’ artefacts are not the only ones worthy of being ‘heritage’.

On a personal level, it amazes me how little I learned about the general history of Bengal and Calcutta in school. We knew all about the Indian Independence Movement, the Harappan civilization, and even bits and pieces about Hitler and the World Wars. What was sorely lacking from my education was the concept that being a part of history was not an honour meant only for the nobles or elites, the gallants or villains. Instead, it is about you and me, our grandparents, our families, our letters, and the spaces we inhabit. The area now known as Calcutta was not transformed in the span of a day by the efforts of Job Charnock. Beginning from fishing hamlets, rivers and creeks, and a Pilgrim’s Path that goes back centuries before Calcutta got its name, the developmental history of the region has often taken a backseat in the face of its colonial and postcolonial narratives.

During the conference, we introduced the students to the city, its history, and why it is how it is – all through visual mediums including maps, old photographs, and paintings. Before they could doze off to the hum of the projector, we led them out into the open and headed to Dalhousie Square on the first day of the workshop. They were suitably impressed on learning how St. John’s Church was built on an old burial ground, how it was overcrowded because of the high mortality among the first waves of Europeans visiting Calcutta in the 1700s, and how malaria, one of the many killers of the time, would be treated using mercury and bloodletting, often killing the sick anyway. St. John’s Church also happens to house Job Charnock’s Mausoleum, whose architecture is anything but European. We were pleasantly surprised when the kids correctly surmised that the local architects of the time probably did not know how to build European-style architecture, and that was the reason for its Indian design.

The next morning the kids were excited about the prospect of another walk, this time to the sites around Kumartuli. The workshop was designed to let them observe the differences in the state of conservation of the built environment in various sections of the city. Our primary aim was to show them places they would not normally have access to, or even notice; by walking the streets, they learned to be more observant and empathetic to the needs of the spaces they populate.

The questions started pouring in once we started walking around Upper Chitpore Road, beginning near Bagbazar Ghat and ending at the Bhagyakul Roy Family Mansions. One of the children’s questions that stayed with me was: “Why should we preserve this building which apparently has no significance other than this woodwork sculpture on top? Why not keep that in a museum, and make the housing conditions more liveable?” This leads us to a larger question – what about creating community museums in Calcutta, or even a Calcutta Museum? Is the single gallery in Victoria Memorial sufficient for our future generations to fall back on? Why should we expect them to fall back on dusty papers and government documents in corridors full of bureaucratic red tape? Should the history of our city, the one we live in, not be available to the people of the city in a form that is relatable, understandable, and memorable?

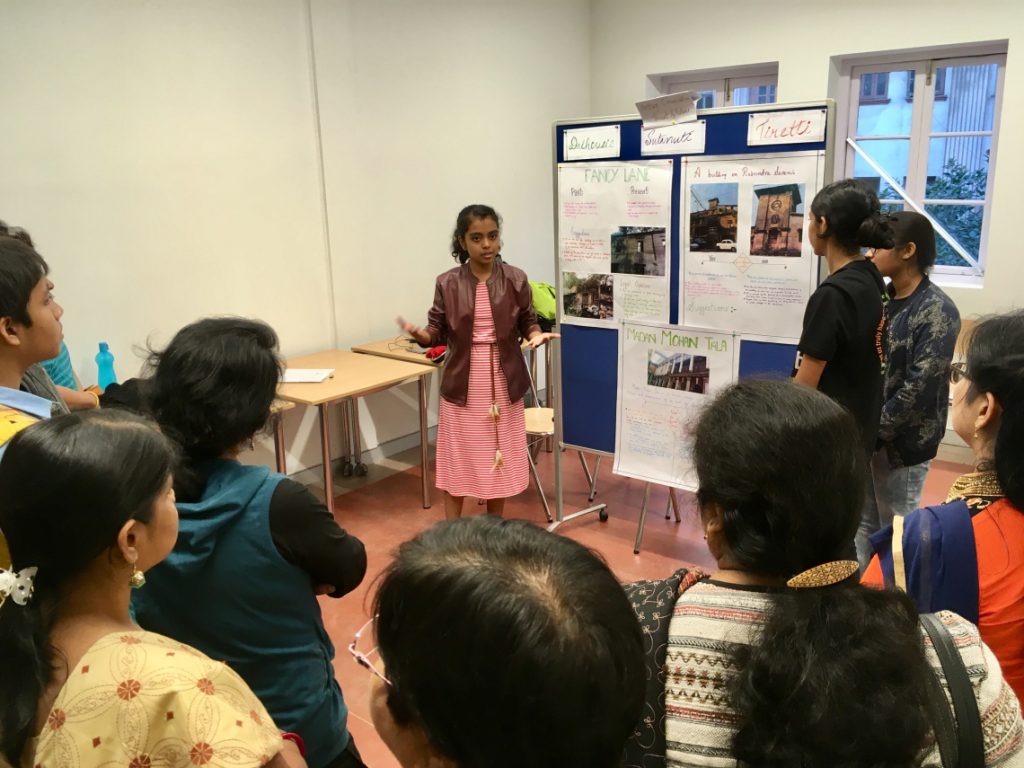

On returning to the Goethe Institut, we had the children dissect the Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s mandates on heritage buildings, including snippets from the KMC Act of 1980. The task was to determine the specific legalities that could be used to improve the situation of the buildings we had seen on the walks, and how the law could be modified to be more flexible and sustainable in the long run. The students were divided into groups of threes and fours so that each could work on a different aspect or site for their final presentation.

It is sometimes distressing when innovation and creativity has to end in an action-oriented audience presentation in a short period of time, but the students masterfully dealt with the twin challenges of time and content. During the prep hour, their questions and concerns started pouring in: who owned the buildings; who owned the artefacts; should there be a dedicated museum for the communities; why are some buildings well-restored while others are falling apart; how can an estate be owned in the name of a god; why do the authorities not accept help from private citizens or involve the community; how can the community come together to achieve the sustainable conservation of sections of the city; and so on and so forth. It was humbling for me to see how much they had understood and unearthed in the short span of one and a half days. Amidst the volley of facts and stories and the sensory overload, the students had found breathing space from their rigorous academic pursuits to pursue lines of independent questioning about their own heritage.

To tie all of the lessons together, the last day of the conference included a visit to the community associations and Taoist temples in the Old Chinatown near Tiretti Bazar, Poddar Court. The community here draws their lineage from five different villages in the Guangzhou region of southern China. The descendants of people from each village have their own club and temple. As a classic example of community engagement, Mr. Lee from the Sei Vui temple and community association talked to the children about the origins of the club and the history of the Chinese immigrants, who were historically an important trading and industrial community in Calcutta. The club dormitory, which served as a resting place for new immigrants from Sei Vui village in the early 1900s, has recently been repurposed into a restaurant. As an excellent example of the reuse of heritage spaces, this visit reinforced the idea that heritage conservation is very possible for the people of this city and those who care about it.

For their final presentations, the three groups of students created: a quiz; a legal review of the current state of certain buildings; and a status report on the state of conservation of different sections of the city. While Group 1 worked on a trivia quiz on historically significant structures, they also came up with questions like “Who owns heritage? And what is our role in conservation?” They did a great job of putting our thoughts into words and presenting them to the parents and teachers who came to participate. Group 2 did a review of Madan Mohan Tala, buildings in various stages of dilapidation on Fancy Lane, and a house located on Upper Chitpore Road. They worked with the varying aspects of ownership and how certain legal functions of a temple estate are different from those of a corporate or private owner. I am glad they decided to work on an oft-misunderstood aspect of the conservation efforts around the city. The members of the third group presented a grading of sites according to their level of risk, regardless of their ownership. They focused on the relevance of heritage sectors in a city, where magnificent structures with forgotten owners deserve to be saved too. Highlighting places like Bishnuram Chakrabarti’s Shibtala and St John’s Church in various stages of the conversation spoke to how much they had retained, both in terms of facts and figures and their visual impressions, including architectural details.

It is difficult to put into words how glad I am to have met these children who worked hard and convinced the general populace that ‘doing’ heritage and heritage walks is a gratifying and necessary objective for a concerned citizen. While it was fun to work with the kids, I have concerns about whether our social bias of pushing children to study science and technology will let them accomplish their own goals of heritage conservation, however small they may be. It also brought forward how the legalities involved in heritage efforts need to be simplified, and that the communities around heritage structures can themselves engage in collecting funds, formulating plans, and giving shape to conservation efforts. A lot remains to be done in terms of heritage identification and mapping, before steps can be taken to ameliorate the condition of the built heritage in the city. Bringing the people of the city together by creating a common digital platform for them to locate and document our built heritage is a very real dream for us. Petitioning the municipal body to disentangle the legalities of grading heritage buildings, or even clarifying the community’s role in sustaining any heritage conservation efforts will help the community come to terms with their heritage and rights to it. This city and the people have a lot of fight left in them. We would like to give their and their children’s hopes a place to find fruition.

Acknowledgements: Goethe Institut-Kolkata, Suvodeep Saha, Srinanda Ganguli, and Chelsea McGill.

Disclaimer: All images used in this post are the ownership of Heritage Walk Calcutta and may not be used without proper permission.

Pritha Mukherjee is a Research and Development Associate at Heritage Walk Calcutta.